Peter C. van Wyck

Peter C. van Wyck is a researcher, writer and Professor of Communication and Media Studies, and Co-Director of the Media History Research Centre at Concordia University in Montréal. His research, writing and photographic work arise from multidisciplinary training in forestry, ecological sciences, environmental and cultural studies, philosophy, and media studies. At Concordia he teaches and supervises in areas of communication and media theory, photographic theory, semiotics, theories of place, and visual culture. He has published and lectured widely on environmental themes including deep ecology, the predicaments of the Anthropocene, and nuclear history and culture.

Inspired perhaps by WG Sebald, he came to photography as a way to develop a writing practice adequate to understanding the complexities of nuclear culture. Seeking to understand the deep and abiding kinship between nuclear practices and photographic technologies, he came to see a similar relation between photography itself and practices of writing.

His recent nuclear-themed writings include the award-winning books Highway of the Atom (McGill-Queen’s UP 2010) and Signs of Danger: Waste, Trauma and Nuclear Threat (University of Minnesota Press, 2005); a photographic essay “An Archive of Threat” in Future Anterior (2012); essays in the edited volumes Thinking with Water and Bearing Witness: Perspectives on War and Peace from the Arts and Humanities (both McGill-Queen’s UP 2013); “The Anthropocene’s Signature,” an essay for The Nuclear Culture Source Book, ed., Ele Carpenter, (Black Dog Books, 2017).

Forthcoming are: “The Lens of Fukushima,” an audio recording and essay with long-standing atomic collaborator and friend Julie Salverson for Through Post-Atomic Eyes, eds., John O’Brian and Claudette Lauzon (McGill-Queen’s UP); and, “Signing the Holocene,” for Critical Topographies, eds., Jonathan Bordo and Blake Fitzpatrick (McGill-Queen’s UP).

Currently he is experimenting with a home-made cloud chamber to photograph radioactive decay (from Trinitite to contaminated food from the Fukushima area); writing an essay on fieldwork as method with Julie Salverson (Queen’s University); tracking the parallel exiles of Walter Benjamin and Paul Klee’s Angelus Novus; and planning field work with Mary Kavanagh to document historical uranium mine sites in the region of Bancroft, Ontario. His next monograph is entitled The Angel Turns: Memos for the End of the Holocene – completing a trilogy of nuclear-themed works begun with Signs of Danger.

Contact

Dr. Peter C. van Wyck

Department of Communication Studies

Concordia University

Montréal, QC

H4B 1R6

[email protected]

[email protected]

https://www.concordia.ca/artsci/coms/faculty.html?fpid=peter-c-van-wyck

Books

Primitives in the Wilderness: Deep Ecology and the Missing Human Subject. Albany: State University of New York Press, 1997.

Signs of Danger: Waste, Trauma, and Nuclear Threat. Vol. 26. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2005.

Highway of the Atom. Montréal & Kingston: McGill-Queen’s Press, 2010.

Texts

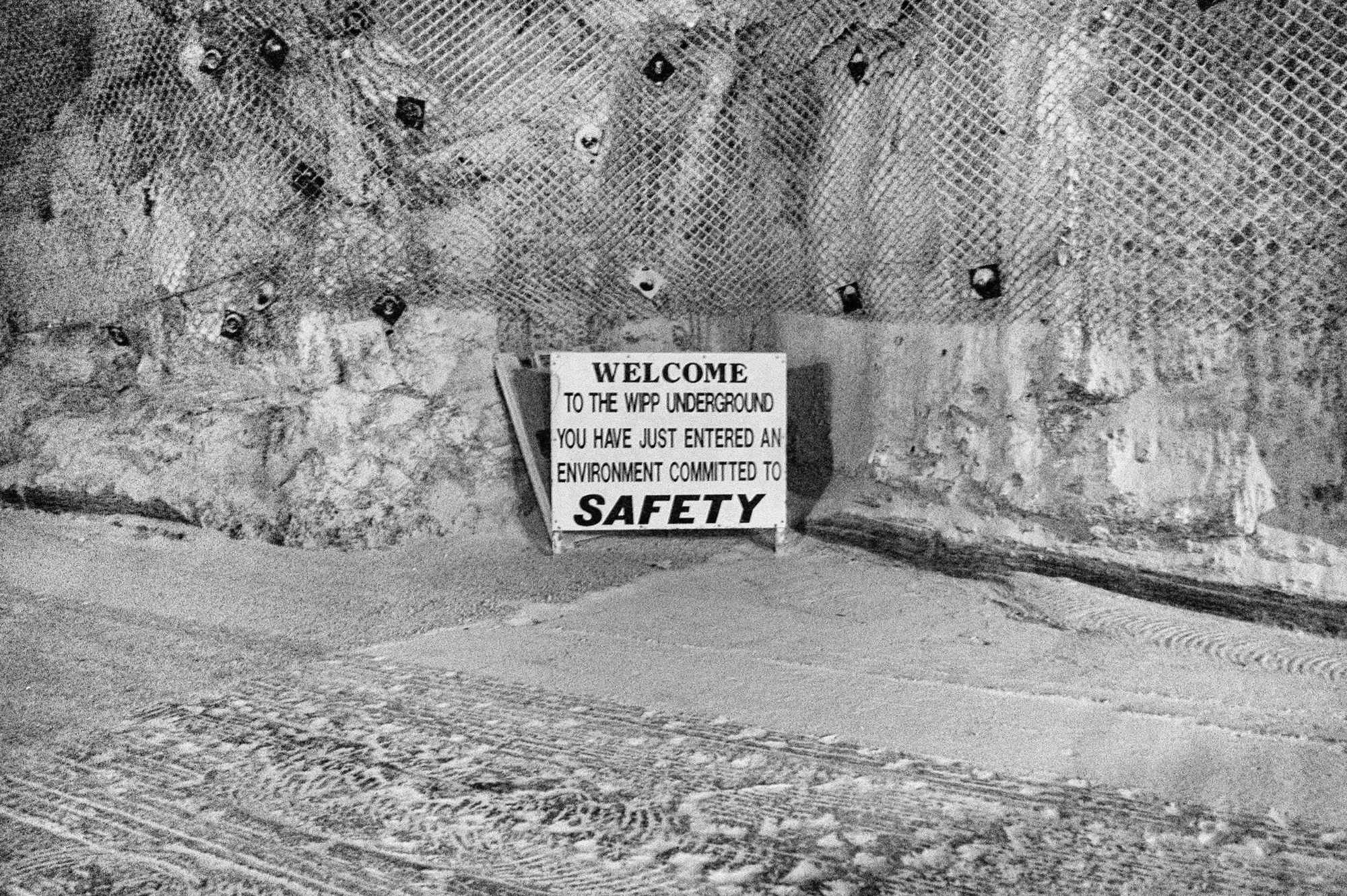

Archive of Threat

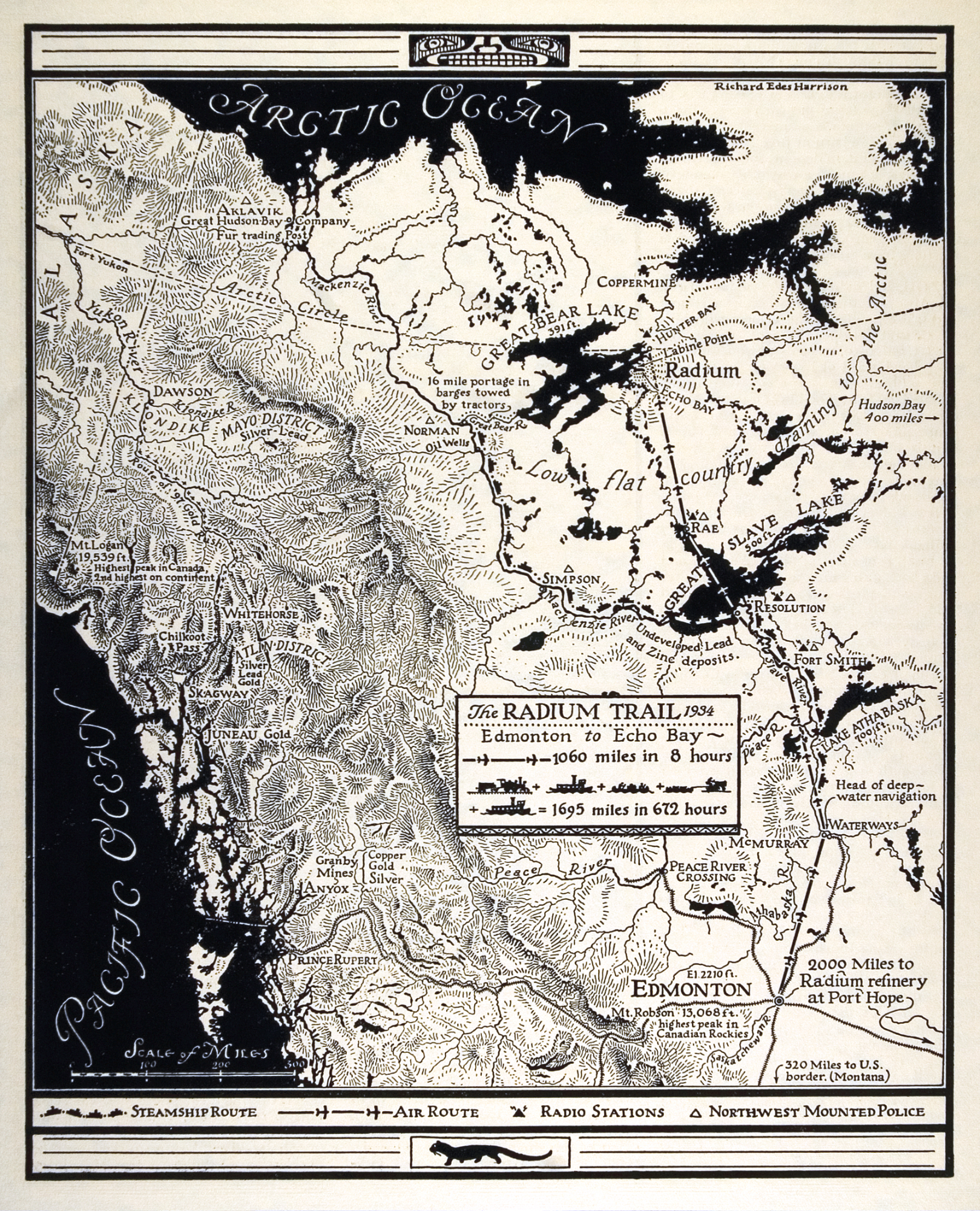

In 2001, I started a project – the highway of the atom – that, amongst other things, turned into a book of the same name that was published in 2010. My impressionistic journeys to the North of Canada sought to identify residues and other forms of leakage. Stains on the land. Some of the leakage is “real,” by which we might mean material, at least in the case of the stain down the Highway of the Atom, measurable in terms of half-lives; boats, barges, building materials, mine tailings, and so on. But some of the leakage doesn’t even this kind of materiality, statistical or otherwise. This kind of leakage might be narrative, or memorial, or archival, or indeed might have the character of a deferred action through some traumatic mechanism—not too difficult to imagine. I approach this not as a history of disaster, but history as disaster. A history which consumes itself, its witnesses, and its evidence. Ghosts. Until very recently the Dene of Great Bear Lake, and many others along the Highway knew nothing of radioactivity. How would one even translate such a concept? In Inuktitut language, I am told, the concept of half-life translates as half-human.Anyway. At the outset, this “highway” references a palimpsestic economic and colonial path or route used initially by Europeans carrying furs, food, and disease, and subsequently carrying radium and then uranium. This material passed through the North of Canada, leaking as it went, to Port Hope, Ontario where the ore was processed and the town contaminated, and then into the productive centres of World War II – the various sites associated with the Manhattan Project – and subsequently extended itself over the clear morning skies of Hiroshima and then Nagasaki, and back again into the community of Great Bear Lake in the form of cancers, stories, addictions, and depression; hauntings. At least this was one possible mode of description; this is where I began.

But this route, this highway, was tricky. In one sense it could be traced on a map – for instance, a line from the far north of Canada to the bomb development facilities in the United States, and then Japan. But as I began to think about it, the route was much more complicated. It was thicker; it spread out in a contrapuntal fashion.

That is, people and events, and boats and trains, and governments and monuments, archives and photographs, and many, many contaminated landscapes. And ultimately the horrific events so weakly contained within the proper names Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

And there were many, many stories to uncover, stories that began to fill in this route. Some of these stories were historical and scientific: the many published and archival documents that describe the details of the mine; the technical scientific achievements that produced the understanding of nuclear materials; the practical aspects of the transportation of radioactive material from a remote northern mine to a refining plant in southern Ontario; the records of the first bomb test – Trinity as it was called; and all the many forms of documentation of August 1945 and beyond.

The meta-data of the Anthropocene, we might say.”